I’m still thinking about the events one

hundred years ago in 1919: the March 1 movement for independence and its

aftermath. I am lucky to live close to many places of historical interest, like Seodaemun prison and

Severance hospital, which are full of history right on my doorstep.

|

| (It was a bad air day - sometimes it happens. I keep my mask ready just in case.) |

|

| Seodaemun prison - view from the north side |

In 1992 the Seodaemun prison was turned

into a museum, the Seodaemun Prison History Hall, to preserve the history of what took place there during the Japanese

occupation and beyond. I have walked by it often, but I never

really thought much about what took place there, so I decided it was time to

stop in and take a look.

|

| tower on the west wall |

Soedaemun prison was built in 1908 as Gyeongseong

prison (which was the Japanese name for Seoul). It was built by colonial

Japanese authorities for the purpose of controlling the local population. Originally

designed to hold 500 people, in the years following the peaceful uprising, the

numbers swelled to nearly five times that number, with prisoners housed in

overcrowded conditions.

|

| interrogation room |

|

| shackles on display |

Among those who were imprisoned at that

time, one was school-girl Yu Gwan-sun (16), who died in September 1920 from the

torture inflicted on her. According to police records discovered in 2011, of

the 45000 who were arrested by Japanese authorities in relation to the

protests, 7500 died from maltreatment.

|

photo of Yu Gwan-sun

public domain https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1a/Yu_Gwan-sun.JPG

|

One of predecessors, Dr. Frank Schofield of

Severance hospital, was an eyewitness to the events. He went around Seoul with

his camera, making a record of the demonstrations to send overseas. As a doctor at Severance, he also ended up

treating many of the casualties. Apparently he

was also able to get access to Seodaemun prison at one point by showing the

business card of the chief of police to the guards. This allowed

him to go in and see the conditions in the prison firsthand.

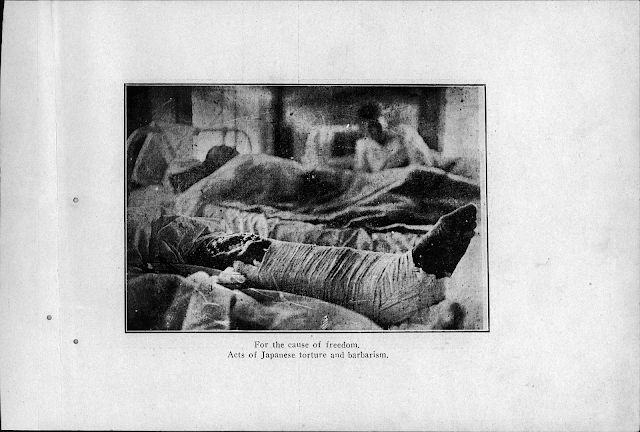

Here are a few photos that appeared in a

Red Cross pamphlet published in 1920 (probably taken by Schofield).

|

public domain: Red Cross pamphlet on the March 1st Movement, 1919, p.

42 “Photo of Korean spectators viewing the Korean flag on the Independence

Arch.” http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/p15799coll126/id/5245

|

|

public domain: Red Cross pamphlet on the March 1st Movement, 1919, p.

19 “Photo of Japanese policeman taking Korean women to prison.” http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/p15799coll126/id/5245

|

|

public domain: Red Cross pamphlet on the March 1st Movement, 1919, p.

17 “Photo of acts of Japanese barbarism.” http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/p15799coll126/id/5245

|

|

public domain: Red Cross pamphlet on the March 1st Movement, 1919, p.

18 “Photo of funeral for those massacred in movement.” http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/p15799coll126/id/5245

|

See also this youtube video on Schofield:

|

| Independence Gate, located now at Dongnimmun near

Seodaemun Prison, was designed in 1897 to be a symbol of the desire of Koreans for independence. It still plays that role. |

Comments

Post a Comment